Are solar parks impacting our food supply?

Crops need sun, but so do solar panels, but are solar parks impacting our food supply when installed on farmland? While farmers and researchers argue there is enough room for both agriculture and solar energy, political efforts to protect the food supply by halting solar park installations on farmland may ironically harm farmers and jeopardize our food security.

Table of Contents

Record lows, all-time highs

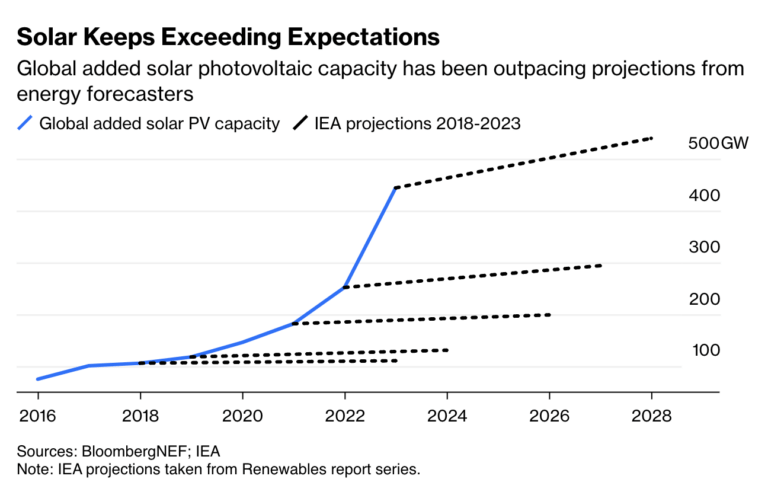

The deployment of solar photovoltaic capacity has consistently been outperforming forecasts, as evidenced by data from BloombergNEF and the IEA.

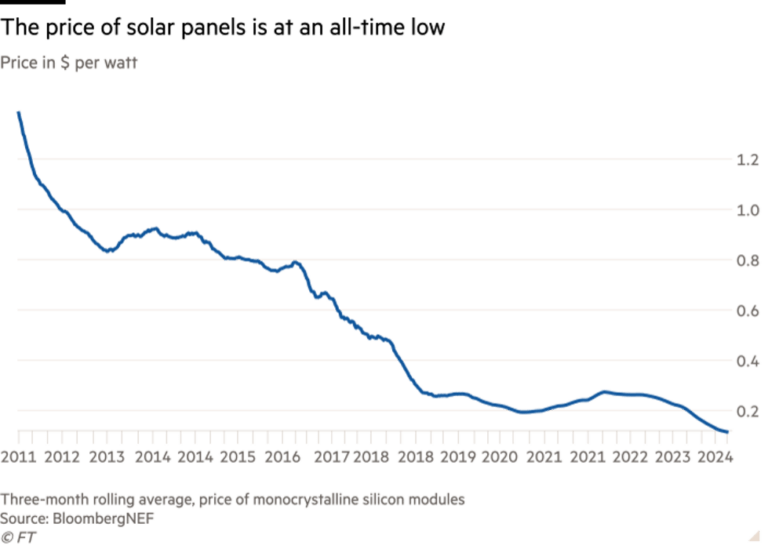

Regular readers will recognize that the primary driver of this solar PV boom is the significantly reduced cost of solar panels. Chinese manufacturers, engaged in a fierce price competition, have driven panel prices to all-time lows, resulting in record high exports. Currently, the EU imports 97% of its solar panels from China.

Given that panels constitute about 30% of the total cost of a solar park, it’s no surprise that developers and EPCs free up liquidity to develop more projects using Chinese-made panels, which can be up to 50% cheaper than their European counterparts.

So, judging by how things are going in terms of deployment, little seems to be standing in the way of solar PV’s continuous ‘shine’, except one thing: Farmland.

Concerns over food supply

Amidst the happy days of record PV deployment, tensions are simmering over the use of agricultural land for solar farms. Opponents argue that using farmland to install solar parks is impacting our food supply. This debate is not new, but it has been reignited by the recent decree from the Italian government, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, banning ground-mounted solar panels on agricultural land. Meloni has justified the ban by claiming that the PV rollout threatens Italy’s “food sovereignty,” a position that many farmers and experts disagree with.

Italy is not alone in scrutinizing the solar industry. In the UK, former Energy Secretary Claire Coutinho has urged local councils to reject solar projects on valuable agricultural land. Recently, a 43-hectare PV project in South Kesteven was rejected by the planning committee, with the chair explaining to the BBC:

“If we don’t provide food grown locally then we are importing it, so we end up again increasing the amount of gases going into our environment. I think at the moment, if we don’t protect our local food supply we end up with increased costs”.

Planning committee chair, South Kesteven District

This trend is echoed across Europe. The Dutch government has paused the development of new ground-mounted solar parks on farmland to minimize environmental impact. Romania has halted approvals for new PV plants exceeding 50 hectares. Similarly, in Sweden, a 128MW solar project by European Energy was recently rejected over agricultural concerns.

In Spain’s Andalusia region, the situation is flipped on its head. Here, farmers are resisting land expropriation for solar projects, but tensions over solar vs. agriculture are nonetheless present.

Fears vs. facts

The fear that PV plants will overrun farmland and jeopardize our food supply calls for a bit of scrutiny. Despite the growing global population and increased demand for food, agricultural productivity has kept pace. Over the past 60 years, crop yields have surged significantly, with some staples seeing a 3.5-fold increase in yields per hectare.

Given these advances in agricultural efficiency, the argument for safeguarding farmland to ensure food security becomes less compelling. Even without considering yield improvements, do the concerns about a compromised food supply hold water?

Plenty of land to spare

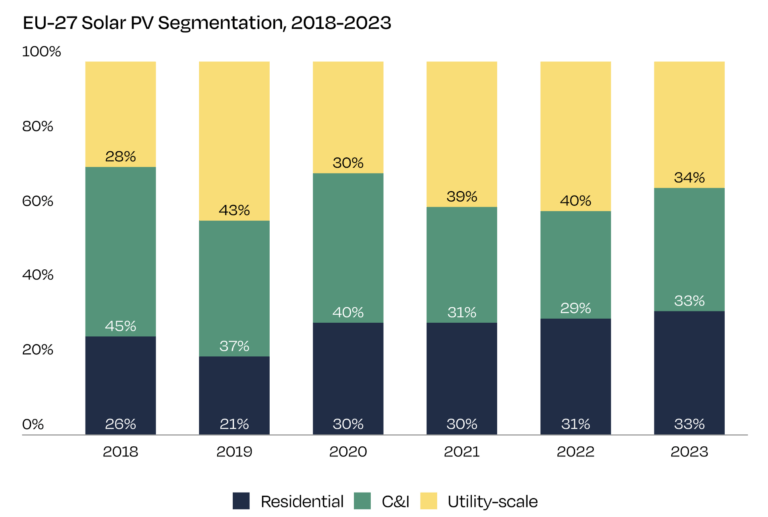

The European Commission’s Solar Energy Strategy aims for 720GWDC of solar power by 2030. Currently, approximately 263GW of installed solar capacity exists across Europe, with much of it not even on farmland. 2/3 of the 56GW installed Solar PV capacity added in 2023 was installed on rooftops. However, with substantial capacity yet to be added, concerns about the impact on agricultural output are understandable.

To put these fears into context, consider the land requirements for achieving this goal. According to Eurostat, Europe has 157.4 million hectares of utilized agricultural area. Assuming 1MW of photovoltaic capacity necessitates 1 hectare, reaching 720GWDC would require 720,000 hectares. In the improbable scenario where only farmland is used and solely ground-mounted PV technology is employed, this would encompass merely 0.457% of agricultural land.

The promise of agrivoltaics

This scenario presumes exclusive reliance on ground-mounted PV. Notably, agrivoltaics— which will allow for certain types of crops to coexist alongside solar installations —provide an alternative. Dutch examples illustrate the feasibility of such coexistence. While agrivoltaics requires more land to generate equivalent output, it enables farmers to continue cultivating crops while earning additional income.

Research from Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE and the University of Göttingen reveals that 72.4% of German farmers are open to adopting agrivoltaics, primarily motivated by the prospect of increased revenue. This positive outlook likely extends beyond Germany.

Solar PV – a gift from the heavens

Farmland lease prices for photovoltaic (PV) installations range between €3,000 to €3,500 per hectare in Europe, a substantial increase compared to the average cost of €357 per hectare. For farmers seeking to safeguard their livelihoods, PV systems offer a lifeline against rising costs and extreme weather conditions that increasingly threaten yields.

Photovoltaics are a salvation for us—a gift from the heavens

Emanuele Bocchicchio, Italian farmer.

The opportunity to lease land to developers can mean the difference between abandoning farming and continuing to produce food. In an interview with the Financial Times in June, an Italian farmer from southern Italy described solar panels as “a gift from the heavens.” The farmer leased 44 hectares of unused land to a developer, earning €3,000 per hectare for land otherwise unsuitable due to warmer weather and lack of irrigation.

Agri-PV: A viable compromise?

Although Meloni’s new bill blocks ground-mounted solar installations on farmland, it spares Agri-PV, allowing farmers some options. However, Agri-PV remains more expensive to build and less mature technologically than ground-mounted systems, stalling new developments in Italy for the time being.

Advocates for installing PV on rooftops, car parks, and brownfields instead of farmland have valid points. This should indeed be a priority for any government. However, consider Italy’s predicament: extreme heat, drought, and rising costs have left about 25% of designated farmland fallow. When growing food is unviable, why block farmers from finding sustainable income alternatives, as Meloni’s new bill does?

The bottom line is clear: we need both solar energy and food (obviously). Pitting these needs against each other may harm the agricultural sector and overlook significant benefits for the planet and people.